- Rule, Britannia, no more?

- Unpopular Opinions: US Quadball Cup 2023

- Proven Contenders: University of Virginia

- Proven Contenders: Rutgers University

- Proven Contenders: University of Michigan

- Proven Contenders: Creighton University

- Different Perspectives: A Look Inside USA Ultimate

- Antwerp QC, Much of Belgian Core, Leaves Competitive Quidditch

Exploiting the Forgotten Front

- By Ethan Sturm

- Updated: September 11, 2014

Credit: Nicole Harrig

Open Space is a new series of articles focused on the developing tactics in our ever-growing sport. In the first edition, we look at the underused square of pitch in front of the hoops on the offensive end and how utilizing it correctly can lead to a more complete attack.

In just about every sport, offenses are looking to utilize open space in the attacking zone. Soccer players are always looking to play a ball into a winger streaking into space; quarterbacks lead receivers with deep passes that take them away from the safeties; and hockey players on the power play will pass and pass until the open man is the one with the puck.

In quidditch, though, that does not seem to be the case. At the highest level, many entire offensive possessions end without a single player making a cut into the area in front of the hoops, even if the defense leaves that space wide open. From early on in the short history of the sport, teams seem to have declared that this area was a beater’s wasteland, a place you simply do not go unless you want to be headed back to your hoops with a nice bludger bruise to show for your troubles.

But as passing has improved in the sport, there is now more of an opportunity to make use of that space than ever before. Can it still be a risky endeavor? Of course, but by learning how to use it right, you can add a dangerous weapon to your offensive arsenal.

History

As recently as World Cup V, quidditch was primarily a hero-ball sport. A team’s most athletic player would bring the ball downfield, pass the point defender and then try to dodge the opponent’s beaters. Succeed, and he had a goal; fail, and it was a turnover. Assisted goals were about as rare as a game actually lasting 10 minutes.

Suffice to say, the sport has come a long way in the past two-and-a-half years. The season following World Cup V came with the widespread use of the two-handed catch, and it was fitting that the University of Texas at Austin took home the World Cup VI title with the smoothest passing game the sport had ever seen. Stephen Bell throwing touch passes for Sarah Holub to catch at full extension behind the hoops was what dreams are made of.

In the time since the Longhorns’ groundbreaking performance in Kissimmee, players have started looking for the space behind the hoops to receive a pass with two hands, making this the finishing tactic for a multitude of teams. Today, just about any team with a ball carrier capable of making that pass will be looking to hit the player cutting behind the hoops.

Unsurprisingly, defenses have taken note. Many teams that play a man defense will not cover a male wing chaser, opting to cover a female chaser operating behind the hoops instead, a concession to the fact that the behind-the-hoops attacker is a more pressing threat. Others have begun to set up their keeper behind the hoops, where he can guard against the distance shots while keeping an eye on any chasers working from behind the hoops. Even zone defenses have adjusted to the behind-the-hoops attack. Emerson College’s zone sets up a female chaser behind the hoops to guard that area, while Baylor University’s defense has a beater readily guarding the area.

Clearly, the next major offensive innovation is far overdue.

Why Now?

It really just comes down to the fact that players are better than ever. First, we all caught with one hand. Then, we learned how to catch with two and how to quickly release the ball into a nearby hoop. Now, most elite players can catch a pass with two hands while moving and release a short-range shot or pass with a single touch. By becoming more and more efficient with release times, chasers can lessen the dominance of the beaters in the center of the pitch. Very few beaters will be able to beat a receiver before they catch and release, and even if they do beat the motion by half a second, almost any referee will let it go.

It also helps that adjustments to defending behind the hoop have left the area in front of it more open than ever. Almost every elite team now plays their beaters vertically instead of horizontally, leaving a lot more space along the flanks to enter the zone. On top of that, chasers are defending with the idea to avoid cuts behind the hoops, not to stop cuts right across the middle of the field.

On top of all of that, defenses are simply getting stronger, smarter and more athletic. Attacking the area behind the hoops only requires a defense to react quickly. If a beater can throw hard, accurate beats; if a keeper is too tall to get a pass over; or if a chaser can cover a lot of ground, it becomes ineffective. But attacking the area in front of the hoops requires the defense to react accurately, changing the point of attack and forcing the defense to make the correct adjustment at every position on the field to compensate. This is a much more difficult art—one that cannot just be compensated for with athleticism—and it is why the area in front of the hoops is ripe for exploitation.

Taking Advantage

The Second Ball-Handler

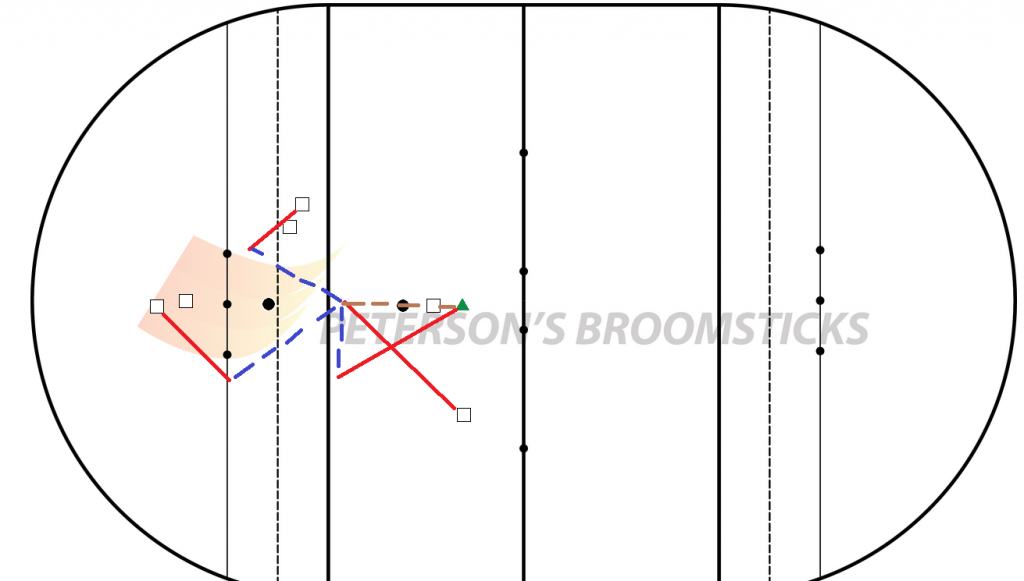

The simplest and most utilized of these strategies involves a second offensive player set up at the top of the offensive zone, a player that against most man-to-man defenses often goes uncovered. The basic goal is to get the ball to a player cutting toward the middle of the zone, between the two beaters to force a beat, and quickly move the ball to an open option.

There are a couple main ways to get this look, the most basic of which is a diagonal cut from the upper wing. One sharp pass will set the play in motion, at which point every player on the offensive should be moving toward the hoops, looking for a pass. Even the original ball-handler should be cutting that way, as there is a decent chance he will be the most open option.

The Horizontal Cut

This is really just a variation on the second ball-handler but is run from a position farther up the pitch. Basically, as a wing chaser, you want to get to a position about even with the edge of the keeper zone and then go right through your defender, a move they will generally not be expecting. If you can get a step on them, you should be able to receive a quick, easily completed pass. At this point, you are headed right toward the opposing teams beaters, but you have all of your options in front of you, including shots toward a hoop of your choice, passes to players cutting toward the hoops or a reset if nothing is developing.

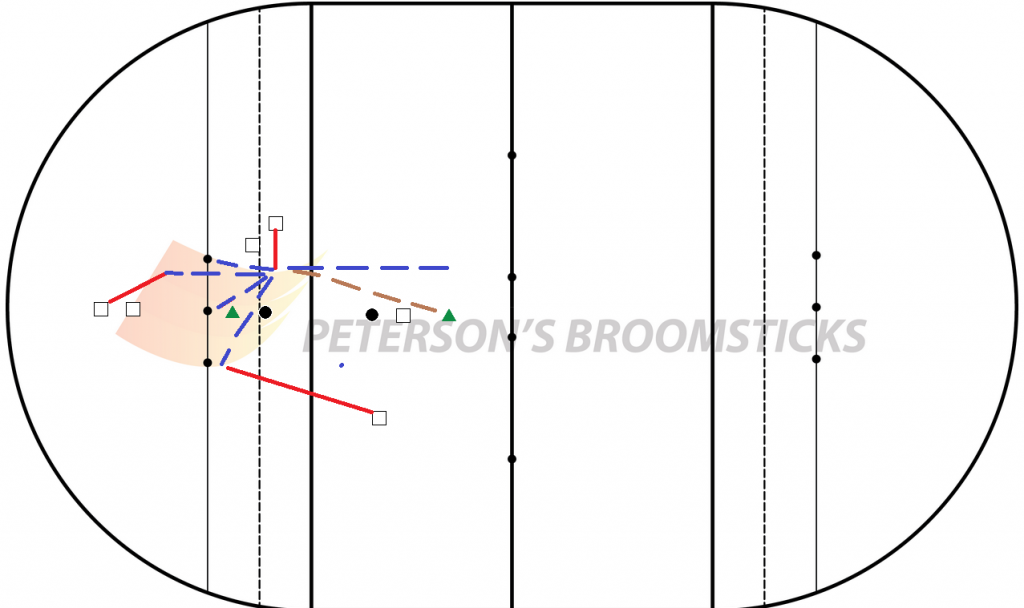

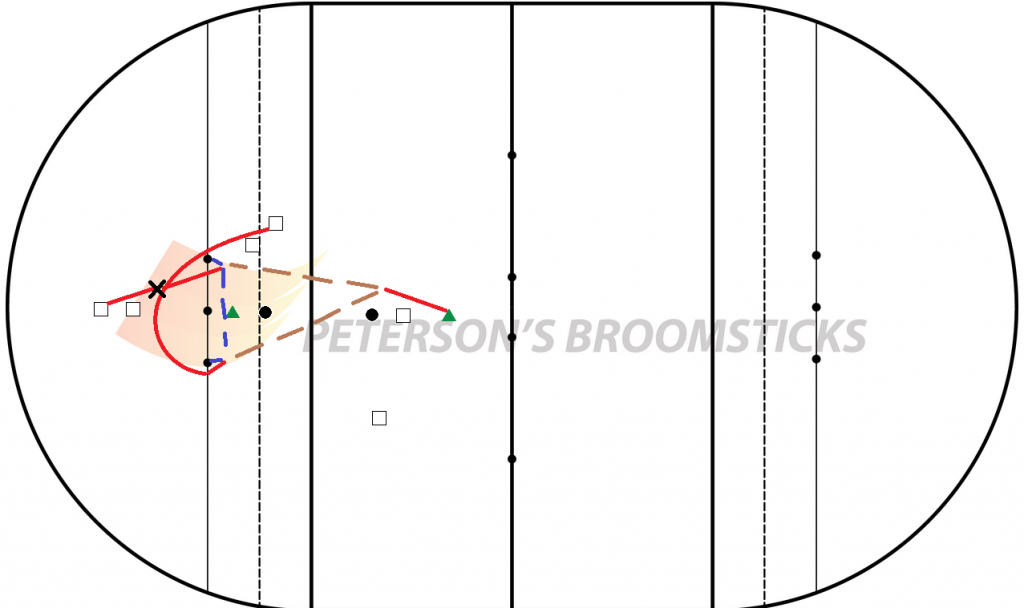

The Maryland Cut

This one is named for the team I see run it more than anyone else. The key player is working from behind the hoops, making a vertical cut straight through the area between the middle hoop and either side hoop to the area right in front of the keeper. A hard pass should be released at the moment the cutter is level with the flat-footed keeper, giving the receiver a distinct advantage to getting the ball.

At this point, you have a player with the ball facing away from the hoops, likely between the keeper and beater. Maryland chasers are trained to throw for a hoop—generally the middle hoop—by turning mainly their upper body. Erin Mallory is perhaps most known for this play. However, if other off-ball chasers are cutting when the initial pass is made, there may be options to draw a beat before dishing off to a nearby teammate for an easy goal.

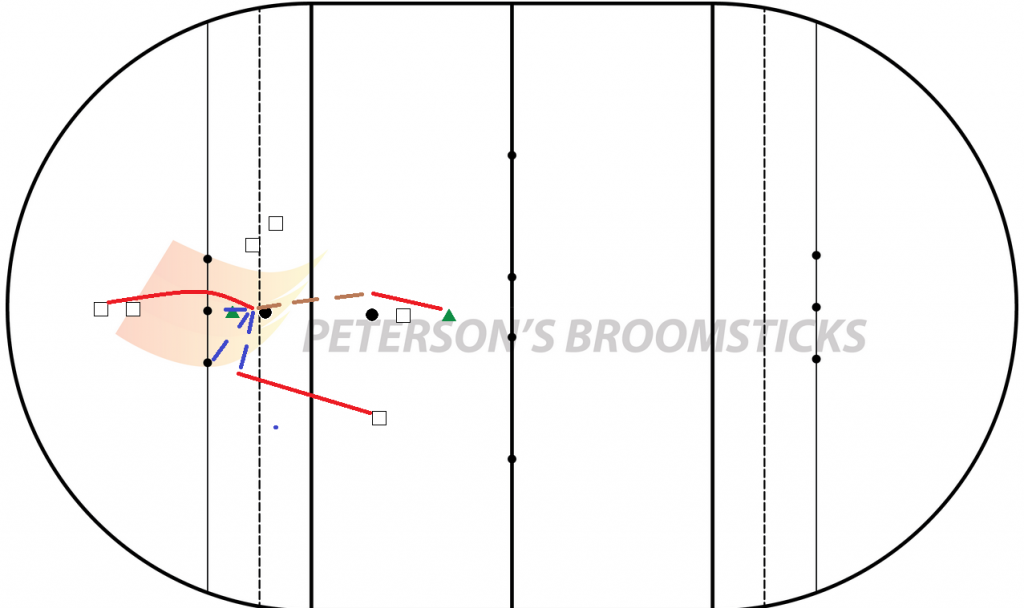

The Wheel

This cut is focused on getting the low winger into space right next to the hoop. Generally, this is done by running a half circle behind the hoops, then cutting in front of the far-side hoop with as little distance as possible between the runner and the hoop rim. The pass to them should be in the air as they are turning the corner, giving their trailing defender no time to get in front and break up the pass. If the ball carrier drives down the opposite wing, they can generally draw the keeper far enough to open up room for the pass.

This play can also be amended with an off-ball pick, creating even more space for the cutting player. This screen will generally be set by the other low quaffle player, who can then roll toward the opposite hoop in case the pick leaves them open.

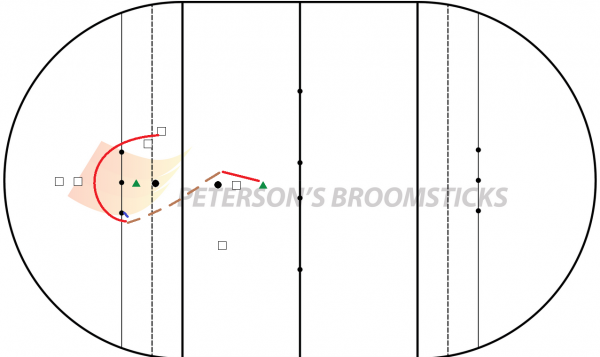

The Post-Up

This setup requires the most specific player to run it. Ideally, the receiver is either very tall, very strong or both. The play is all about positioning: you need to win the shoving battle down low, either to frustrate the keeper and make him useless or to make sure you get to an incoming pass before your defender. The receiver can post up at any of the hoops, but the strategy for the middle hoop is different than that for the side hoops.

If you are posting up in front of the middle hoop, you are not really a scoring threat. Instead, you are serving as both a screen for the keeper on any mid-range shots and as a middleman for the offense, capable of receiving a pass and quickly unloading it to another dimension of the offense. Any points scored from the center hoop position generally involve getting up higher than the keeper on a floated pass and finishing through the tall hoop.

If you post up in front of one of the two side hoops, you become a pure scoring threat. You generally want to set up here if you have a decisive physical advantage over your defender. If you can outplay your defender and have a ball carrier that knows how to give you a hard, direct pass, it will generally lead to points. If something goes wrong, such as a bobbled catch, everyone else on the team, including the passer, should be cutting toward the hoops for a quick pass.

Putting It Into Practice

Outside of simply running repetition drills on each of these routes until your players develop a level of comfort with them, the simplest drill you can run to become more effective in front of the hoops is a rapid release drill. Have all of your chasers stand in a small circle and rapidly catch and throw the ball around randomly, with everyone always using two hands. If you want to switch up the drill a bit, run it like the classic game, Taps, where a player has to jump when the ball is coming to them and catch and release it before they hit the ground.

Conclusion

The middle of the quidditch pitch continues to be underused offensively due to a series of outdated notions of how our sport should be played. But there are numerous ways to take advantage of this space, and, with a little practice, it is possible to add whole new dimensions to how your team plays the sport.

Graphics created using Petersons’ field editor.

About Ethan Sturm

Ethan is the co-founder and former managerial editor and chief correspondent of The Eighth Man. When not talking quidditch, which is rare, he can be found drilling people's teeth and spending time with his elusive wife. He's also the worst.

One Comment