- Rule, Britannia, no more?

- Unpopular Opinions: US Quadball Cup 2023

- Proven Contenders: University of Virginia

- Proven Contenders: Rutgers University

- Proven Contenders: University of Michigan

- Proven Contenders: Creighton University

- Different Perspectives: A Look Inside USA Ultimate

- Antwerp QC, Much of Belgian Core, Leaves Competitive Quidditch

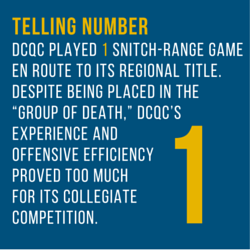

Having dominated against collegiate competition in the Mid-Atlantic, DCQC has yet to prove itself in interregional play, compiling an underwhelming 2-4 record against out-of region teams during the fall. Out-of-range losses to Rochester United and The Warriors show that DCQC has yet to play a competitive game against an established community team and has struggled against experienced competition.

Having dominated against collegiate competition in the Mid-Atlantic, DCQC has yet to prove itself in interregional play, compiling an underwhelming 2-4 record against out-of region teams during the fall. Out-of-range losses to Rochester United and The Warriors show that DCQC has yet to play a competitive game against an established community team and has struggled against experienced competition.

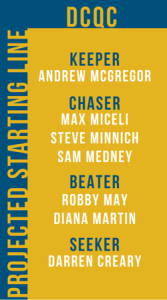

Part of the problem comes from DCQC’s over-reliance on a few core players. Despite a full 21-person roster, Max Miceli, Andrew McGregor and Steve Minnich all played the vast majority of minutes in every game for DCQC at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Championship. Other than Darren Creary, who gets a shift or two at keeper before  switching to seeker, no other chaser receives an extended run of playing time. While no one is questioning the talent and pedigree of DCQC’s first line, the squad’s hesitancy to even play reserves in well out-of-range games against the likes of VCU shows the lack of faith this team holds in its second unit and puts a continuous strain on their first line. While the likes of Pierson Geyer and Dan Newton are not game changers, they are competent and experienced role players that can contribute meaningful minutes in a tight game. While DCQC could over-rely on Miceli and McGregor to best less inexperienced Mid-Atlantic teams, these players cannot be expected to play entire games against more experienced and more physical teams from other regions. New addition Cory “Apple” Apps provides another option off the bench, but if DCQC is to challenge teams like The Warriors or Quidditch Club Boston, it needs to show faith in more than just him. By allotting its secondary chasers more playing time, DCQC can reduce the workload of its stars, allowing them to perform at their highest level for the multiple high-intensity games the team will be expected to play at US Quidditch Cup 9.

switching to seeker, no other chaser receives an extended run of playing time. While no one is questioning the talent and pedigree of DCQC’s first line, the squad’s hesitancy to even play reserves in well out-of-range games against the likes of VCU shows the lack of faith this team holds in its second unit and puts a continuous strain on their first line. While the likes of Pierson Geyer and Dan Newton are not game changers, they are competent and experienced role players that can contribute meaningful minutes in a tight game. While DCQC could over-rely on Miceli and McGregor to best less inexperienced Mid-Atlantic teams, these players cannot be expected to play entire games against more experienced and more physical teams from other regions. New addition Cory “Apple” Apps provides another option off the bench, but if DCQC is to challenge teams like The Warriors or Quidditch Club Boston, it needs to show faith in more than just him. By allotting its secondary chasers more playing time, DCQC can reduce the workload of its stars, allowing them to perform at their highest level for the multiple high-intensity games the team will be expected to play at US Quidditch Cup 9.

DCQC’s offense runs through the hands of Miceli and McGregor. The two former UNC players are content to run a patient offense; toss the ball back and forth; and wait for a potential mismatch before driving for a shot or quick dish to a teammate next to the hoops. Even if a team can prevent the drive, both possess accurate arms and the ability to drain the long shot. Complementing this duo is the towering 6’7” frame of keeper Creary, who becomes the team’s primary offensive threat when he enters the game as Miceli will look to feed him alley-oops behind the hoops. At times, DCQC can become overly reliant on this strategy and its offense will stall as the defense figures out how to contain Creary and defend Miceli.

Defensively, DCQC leaves much to be desired. After experimenting with a zone defense earlier in the season, the team has reverted to a standard man-to-man chaser defense. Old warhorse Minnich, DCQC’s stalwart point defender, is one of the most consistent and aggressive tacklers in the Mid-Atlantic. Beyond Minnich, DCQC’s chasers lack toughness. Keepers McGregor and Creary will block shots but neither is likely to leave their hoops to make a hit. A team that can create bludgerless opportunities on offense will have plenty of opportunities to score against this team.

DCQC’s biggest question mark currently resides in its beating game. The loss of its best male beater in Carlos Metz to the U.S. Navy is a major blow to DCQC’s beating corps, which will now rely primarily on the arm of coach James Hicks and veteran Robby May (whose attendance at US Quidditch Cup 9 is questionable).

DCQC’s biggest question mark currently resides in its beating game. The loss of its best male beater in Carlos Metz to the U.S. Navy is a major blow to DCQC’s beating corps, which will now rely primarily on the arm of coach James Hicks and veteran Robby May (whose attendance at US Quidditch Cup 9 is questionable).

Hicks loves to throw, and his inconsistency in hitting his target will cost his team against more experienced beater corps. The team will be hoping former University of Richmond beater Derek Roetzel can provide relief for Hick’s overworked throwing arm, but that will depend on how quickly Roetzel can integrate himself into the team after an extended period of time away from the game.

DCQC does find itself with a nice array of female beating talent, which allows them the ability to run the rare two non-male beater setup. Katryna Hicks and Diana Martin are two small but quick beaters while Natasha Connerly provides an aggressive physical presence that allows her to maintain bludger possession and fight off opposing beaters.

At the Mid-Atlantic Regional Championship, DCQC was able to mask its defensive inefficiencies with a composed beating game and a high-percentage offense. But with recent upheaval in the beater position and a poor record against out-of-region competition, questions remain about how high DCQC’s potential is and whether it can make a serious run in bracket play come April.

The biggest difference between the 2014-15 RPI team and its current iteration is that not a single contributing player has sustained a major injury–yet.

RPI has a patient, motion-based offense that guarantees each of its chasers the opportunity to contribute. While typically an offense like this would allow for any player to be inserted into the lineup with little dropoff, under the captainship of Mario Nasta and Teddy Costa, RPI has developed a starting line that is amongst the strongest in the  Northeast. Vibhav Kalaparthy, Sam Nielson and Costa play brilliantly together, and Nasta and Ashtyn Coyle are phenomenal playmakers. But an injury to any of them due to overuse could end their dark horse bid at US Quidditch Cup 9 before it has even begun.

Northeast. Vibhav Kalaparthy, Sam Nielson and Costa play brilliantly together, and Nasta and Ashtyn Coyle are phenomenal playmakers. But an injury to any of them due to overuse could end their dark horse bid at US Quidditch Cup 9 before it has even begun.

RPI, however, has the talent waiting there on the bench. In limited minutes at Keystone Cup II, chaser Michael Li, beater Ashley Dolan and beater Matt Johnson have shown great potential and knowledge of RPI’s play style. Chasers Patrick Martin and Michael Shaw have impressed in performances in previous seasons as well. They may not be as talented as Costa or Nasta, but having them languish on the bench prior to the Cup will not help the team if it looks to make a deep run on day two.

The RPI offense is built around the athleticism of its starting line and has become a well-oiled machine capable of running up the score against any team caught flat-footed on defense. While the team’s bludger-control offense is quick and focused on exploiting mismatches, the players are also are quite astute at slow-balling while attempting to regain control. Using a triangle offense, RPI sits on one side of the field, making four- to five-yard passes while being protected by Nasta’s beating. As seen in their World Cup 8 game against Baylor University, this offensive set is proficient at slowing the game down to a crawl, but is also highly efficient in making teams impatient and forcing a beater into a one-on-one with Nasta, a matchup that only a few players in the country can win consistently. This forces teams to decide whether the loss of bludger control is worth stopping the quick drive-and-dish score RPI has mastered so well.

To beat RPI, you need to outrun them on both sides of the ball. A better-conditioned team ready to put out fresh chasers on RPI’s quaffle carries—particularly Costa or Kalaparthy—can cancel any offensive advantage RPI might have. Against the Remembrall’s triangle offense, a full team effort is needed defensively. An aggressive, accurate beater will be needed to contain Nasta while two or three defensive chasers aggressively attack RPI’s chasers and force them out of their comfort zone. RPI’s players are athletic, but none of them are particularly big, making larger, more physical teams ideal for exploiting RPI’s lack of size.

Furthermore, as talented as Nasta and Coyle are as a beater pair they are beatable if you play patiently against Nasta’s attempts to regain control. Defensively, RPI’s beater game is often too focused on retaining control to depart from the keeper zone, allowing patient offenses the opportunity to drive or take a high-percentage shot on goal. The squad’s smaller chasers are great tacklers and play fantastic coverage but are susceptible to over-committing and being taken out too quickly by opposing beaters. With only one decently sized offensive player, larger opponents should be able to drop enough points to keep RPI in range.

Furthermore, as talented as Nasta and Coyle are as a beater pair they are beatable if you play patiently against Nasta’s attempts to regain control. Defensively, RPI’s beater game is often too focused on retaining control to depart from the keeper zone, allowing patient offenses the opportunity to drive or take a high-percentage shot on goal. The squad’s smaller chasers are great tacklers and play fantastic coverage but are susceptible to over-committing and being taken out too quickly by opposing beaters. With only one decently sized offensive player, larger opponents should be able to drop enough points to keep RPI in range.

RPI is simultaneously a highly desireable pot two matchup and a dark horse Elite Eight contender based on how seriously its opponents choose to take it. With a little bit of development of its backup players and talented freshman seeker Tyler Beckmann, this team has the capability of stringing together a few snitch-ranged upsets on day two before ultimately being taken down by a more physical Southwest squad or a Western community team.

Lock Haven University set its own standards high by upsetting Penn State at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Championship and keeping District of Columbia Quidditch Club in range (the only team to do so at the tournament). Now it has a tall order to fill and less ability to do so.

Lock Haven University set its own standards high by upsetting Penn State at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Championship and keeping District of Columbia Quidditch Club in range (the only team to do so at the tournament). Now it has a tall order to fill and less ability to do so.

A program just starting to see its potential, Lock Haven is not an opponent you want to draw for an easy match. But in order for them to be impactful in April, the team needs to develop its strategy beyond the basics. Lock Haven has historically been a team of athletes, and just this year has filled out, so to speak, and become a real team with chemistry, strategy and depth.

It remains to be seen if the changing of the guard after winter graduations will change its team dynamic. Beaters Zach Whitsel, Caitie Probst and Randy Pruden along with chaser Sarah Ashworth graduated this December but remain with the team. That being said, the captaincy at Lock Haven has transferred from Whitsel to veteran AJ Radle, with Alex Garancheski being the other captain both semesters. Will the team look out for its future, giving younger players more playing time and experience? Or will it try to go out with a bang, giving the majority of the playing time to its already graduated or senior members?

It remains to be seen if the changing of the guard after winter graduations will change its team dynamic. Beaters Zach Whitsel, Caitie Probst and Randy Pruden along with chaser Sarah Ashworth graduated this December but remain with the team. That being said, the captaincy at Lock Haven has transferred from Whitsel to veteran AJ Radle, with Alex Garancheski being the other captain both semesters. Will the team look out for its future, giving younger players more playing time and experience? Or will it try to go out with a bang, giving the majority of the playing time to its already graduated or senior members?

One way to circumvent this issue is to take this semester and use it to train for the variety of gameplay styles Lock Haven will see in Columbia. It has already proven it can develop team-specific strategy against opponents, but it needs to develop more complex strategy in order to make a push at US Quidditch Cup 9. Specifically, having set play with pick and rolls, handoffs or rapid ball movement will help it stay in games it may not have been in last year. Coming up with these staples to add to its offense can possibly turn around the momentum in a game, as it provides stability in what could be a chaotic weekend.

Lock Haven has tasted success and now it wants more. Do not underestimate this squad. The players put the time in for practice and scouting, which means you may want to have a trick up your sleeve. Versatile weapons such as Tyler Potoski at keeper, chaser or beater or Josh Moules at chaser and seeker help make sure Lock Haven is not a one-trick pony. To combat this, develop strategies that will make your typical style seem different, such as handoffs versus pick and rolls, or perhaps have a trick play up your sleeve to throw off momentum.

Lock Haven has tasted success and now it wants more. Do not underestimate this squad. The players put the time in for practice and scouting, which means you may want to have a trick up your sleeve. Versatile weapons such as Tyler Potoski at keeper, chaser or beater or Josh Moules at chaser and seeker help make sure Lock Haven is not a one-trick pony. To combat this, develop strategies that will make your typical style seem different, such as handoffs versus pick and rolls, or perhaps have a trick play up your sleeve to throw off momentum.

We will see if the change in leadership changes the team’s style of play, but it is doubtful. Typically the team likes to play its beaters conservatively on defense, but it has the potential to play aggressively, if not wildly. It all depends who is plugged in at beater. Lock Haven of old put players in with cannons for arms and had to cope with misfires and lost balls frequently. Is it willing to sacrifice its success by going back to what it knew before?

We will see if the change in leadership changes the team’s style of play, but it is doubtful. Typically the team likes to play its beaters conservatively on defense, but it has the potential to play aggressively, if not wildly. It all depends who is plugged in at beater. Lock Haven of old put players in with cannons for arms and had to cope with misfires and lost balls frequently. Is it willing to sacrifice its success by going back to what it knew before?

On the other side of the pitch, led by veterans Jonyull Kosinski and Garancheski, the team’s chaser corps will look to hit if need be, going an eye-for-an-eye early on. Don’t be surprised if your game turns into a physical one when coming down to the wire against Lock Haven. Any whiff of victory and it will claw its way back into the game and clutch seeking will do the rest.

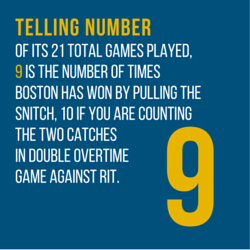

It’s no secret Boston University knows how to put up the quaffle points, but do the Terriers know how to pull the snitch? The answer might surprise you considering the team’s 16-5 record. Just nine of those 16 wins cite Boston as responsible for the game-ending grab, meaning roughly half of the team’s wins are from outscoring its opponent.

To put this further into perspective, of the few SWIM games the team has played, four were against Tufts University. In just one of those games did the Terriers manage to pull the snitch.

Running up the score to the point where the other team cannot realistically come back is sometimes a viable strategy, but, unfortunately, that may not pan out for Boston at US Quidditch Cup 9. Sure, the team has the potential to keep up with some of the stronger high- to middle-tier teams, but if it doesn’t want to run itself ragged or risk losing to an opponent that can score just as well, it will need to find a new seeker. And fast.

People often tout that the Northeast offers the best beaters in the country. However, the best beaters mean nothing if they do not have chasers that can put points on the board. Thankfully for Boston, its chasers are more than capable of doing just that.

Boston’s beaters and chasers complement one another by playing in a similar, aggressive style. Peter Cho and Max Beneke are unafraid to to advance as far as necessary to ensure a goal for their side. Similarly, the Terrier chasers have a tendency to push the ball up and look for the fast cut behind the hoops or allow their beaters to clean up and create openings for hard drives.

Due to the top-to-bottom athleticism of Boston, this aggressive style has worked. Out of the seven other Northeast college teams attending US Quidditch Cup 9, Boston is arguably the most athletic. Against lesser athletes, this style will continue to work favorably, however, if matched up against teams like Lone Star Quidditch Club, University of Maryland and University of Michigan, Boston may not have much success.

Due to the top-to-bottom athleticism of Boston, this aggressive style has worked. Out of the seven other Northeast college teams attending US Quidditch Cup 9, Boston is arguably the most athletic. Against lesser athletes, this style will continue to work favorably, however, if matched up against teams like Lone Star Quidditch Club, University of Maryland and University of Michigan, Boston may not have much success.

Rochester United, a team of equal if not greater athleticism, beat Boston out of range and one could argue United is nowhere near the most athletic team in quidditch. Boston also struggled to find wins against New York Quidditch Club and Tufts University, despite edging both teams out athletically. New York and Tufts were able to find these wins partly because of each team’s fantastic seekers, but also due to the fact that these teams are simply more well rounded. Kyle Jeon and Ethan Sturm are both intelligent minds in the quidditch realm that have helped build their respective teams and develop the strategies they needed to be the presence they are in their region. I’m not sure that current-day Boston has that, and the squad’s lack of a defined strategy will hold it back.

What Boston does have, however, is chemistry—something that is crucial to the success of any team. Over new or rebuilding teams Boston has an advantage due in part to how well all of its players know each other and can play with one another. You saw it with a mostly new Emerson College squad last season that poor team chemistry can cripple a team. Boston knows its strengths and abilities well, and every player makes moves that support one another. The time that many of these players have spent playing with each other is evident and translates to the pitch naturally. Boston gives off a feeling of confidence with this chemistry and is enough to intimidate other less-experienced teams that it can capitalize off of to swing the momentum of its games in its favor.

What Boston does have, however, is chemistry—something that is crucial to the success of any team. Over new or rebuilding teams Boston has an advantage due in part to how well all of its players know each other and can play with one another. You saw it with a mostly new Emerson College squad last season that poor team chemistry can cripple a team. Boston knows its strengths and abilities well, and every player makes moves that support one another. The time that many of these players have spent playing with each other is evident and translates to the pitch naturally. Boston gives off a feeling of confidence with this chemistry and is enough to intimidate other less-experienced teams that it can capitalize off of to swing the momentum of its games in its favor.

With US Quidditch Cup returning to pool play, however, the Terriers’ odds of making bracket play are much higher. But to make it much further, this team will need athleticism and a little luck on its side.

Correction: Our Telling Number states Boston played a double overtime match against RIT. It should state “…if you are counting the catch in overtime against University of Miami.”

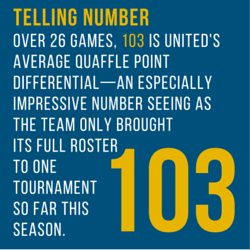

Last summer, as teammates on the Rochester Whiteout, the line of Jon Jackson, Shane Hurlbert and rookie Solomon Gominiak combined to score over 70 percent of the team’s goals. Despite their obvious on-field chemistry and proven

success, this line combination rarely found themselves together on the field for Rochester United. This may, in part, be due to Hurlbert playing a decreased number of minutes as he prioritizes coaching over playing.

With a out-of-snitch-range loss to QC Boston hanging over United’s heads due primarily to a lack of offensive production, Hurlbert should not be afraid to increase his own minutes on-field with Jackson and Gominiak, as his playmaking ability is amongst the best in the Northeast.

To begin, let’s discuss the stars.

Hurlbert will never get enough credit for what he contributes to his team’s offensive production. Lost in the hubbub of World Cup 8 was an MVP performance by the then University of Rochester keeper: He scored an average of three or more goals in each game. His ability to break all but the strongest of tackles, command an offense and play every possible defensive role makes him a matchup nightmare, made only more acute now that he is surrounded by a plethora of gifted teammates.

On United, Hurlbert shares the field with Jackson, formerly of Harvard University, who spent two years drawing double or triple coverage as the focal point of Harvard’s team yet still managed to earn a reputation as one of the most dangerous quaffle players in the Northeast. With Hurlbert and Jackson together, teams need to prepare for their ankle-breaking cuts and broken tackles, as well as their ability to find an open chaser for the quick score. Simply committing a beater to stopping one or both of them may not be enough either, for Jackson’s patience and Hurlbert’s athleticism render any aggressive beater play obsolete.

The rest of the team’s chaser rotation is a collection of talented, driven players able to complement each other due to previous experience playing together. Alyssa Giarrosso has quietly become one of the best female chasers in the Northeast, and her defensive versatility—she’s no slouch as a point defender against all but the quickest ball-handlers as well as superb at off-ball defending—can shut down offenses that underutilize offensive beating. Gominiak, with less than a year of experience, is already one of the better tacklers in the game and an aggressive wing chaser who can carry one or two defenders with him as he drives for a goal. Furthermore, keeper/chaser Brian Herzog, utility player Dan Gagne and chaser Devin Sandon are unselfish and uncompromising players who provide solid defensive support and are fantastic scorers in their own right.

The rest of the team’s chaser rotation is a collection of talented, driven players able to complement each other due to previous experience playing together. Alyssa Giarrosso has quietly become one of the best female chasers in the Northeast, and her defensive versatility—she’s no slouch as a point defender against all but the quickest ball-handlers as well as superb at off-ball defending—can shut down offenses that underutilize offensive beating. Gominiak, with less than a year of experience, is already one of the better tacklers in the game and an aggressive wing chaser who can carry one or two defenders with him as he drives for a goal. Furthermore, keeper/chaser Brian Herzog, utility player Dan Gagne and chaser Devin Sandon are unselfish and uncompromising players who provide solid defensive support and are fantastic scorers in their own right.

The beater rotation for United is exactly what you’d expect from a Rochester team: quiet, efficient and soundly strategic. With 25 years of combined experience, it is exceedingly rare to find a beater rotation that understands the game better than them. Where they falter, though, is their lack of athleticism. As talented as Josh Kramer, Kyle Savarese and Patrick Callanan are, none of them are strong enough to outplay teams of equal beater experience. While each of them have traits that contribute to elite beating  (Kramer’s speed and agility, Savarese’s cannon arm,and Callanan’s outstanding offensive play), none of them present a full package, which can be easily exploited by forcing them to play against their strengths. The team also has a drop-off between their first- and second-string female beater, enough so that a dual-male set may be what is needed if Rochester United looks to spring an upset on a top-five team.

(Kramer’s speed and agility, Savarese’s cannon arm,and Callanan’s outstanding offensive play), none of them present a full package, which can be easily exploited by forcing them to play against their strengths. The team also has a drop-off between their first- and second-string female beater, enough so that a dual-male set may be what is needed if Rochester United looks to spring an upset on a top-five team.

United is a team for which you absolutely need a gameplan. At any given time, opposing teams need to know which chaser is uncovered and shift their beater and keeper coverage to account for it. United’s players are smart enough to capitalize on any mismatches and will only get smarter as their chemistry builds.