- Rule, Britannia, no more?

- Unpopular Opinions: US Quadball Cup 2023

- Proven Contenders: University of Virginia

- Proven Contenders: Rutgers University

- Proven Contenders: University of Michigan

- Proven Contenders: Creighton University

- Different Perspectives: A Look Inside USA Ultimate

- Antwerp QC, Much of Belgian Core, Leaves Competitive Quidditch

It’s Time to Bring Back the (College) Autobid

While USQ tournaments just started in the Southwest and West in the past two weekends, the regional championship season has arrived in the rest of the country. The 2019 Northeast Regional Championship kicks off fall regional season this Saturday, making it the second-earliest regional in the modern qualifying era.

This year’s seven regionals have 40 qualifying bids to USQ Cup 13 distributed among them, based on the relative proportion of teams in each respective region. This left the Northeast, Great Lakes, Midwest and Mid-Atlantic with seven bids; the Southwest with six; the West with four and the South with two. While this distribution is mathematically fair, with larger regions receiving more bids, it fails to take into account the relative strength of each region—meaning that for some teams, the chances of them receiving a bid depend more on which regional they’ll compete at than the quality of their talent and performance.

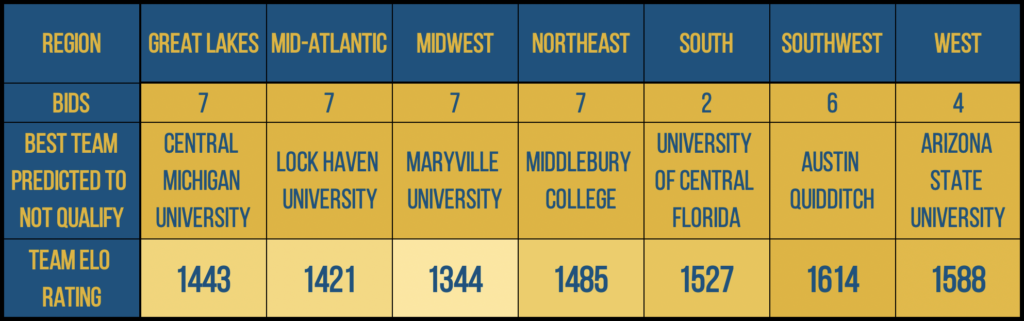

An easy way of telling which regions (and what teams) may or may not be hurt by this current bid system is simply by ranking teams competing at each regional by their current Elo rating, and finding the Elo rating of the first team predicted to not receive a bid, if all results go chalk at their regional championship. While this system isn’t perfect–upsets at regionals can and do happen, and a team’s Elo rating may change significantly over the course of the season–it tends to do a good job of removing outlier teams and predicting which regions will be hurt by the current bid format, since average region Elo ratings tends to remain consistent from season-to-season, and outlier teams have little-to-no-effect on what team ends up missing out on a bid. Looking at only Elo ratings, you get the following predicted results:

Based on these results, it is clear that teams in the Southwest, West and South are hurt by the relative quality of teams in their regions, while teams in the Midwest, Mid-Atlantic and Great Lakes benefit from the assortment. In fact, Austin Quidditch–who is currently the highest-rated team predicted to not receive a bid to nationals at their regional–would be predicted to take third at the Midwest or Mid-Atlantic Regional Championship and win the South Regional Championship. Yet because they play in the Southwest, they have a significant chance of not even qualifying. Even if Austin does leave Baton Rouge with a bid in February, it is almost guaranteed that a similarly-calibered team from the Southwest will miss out.

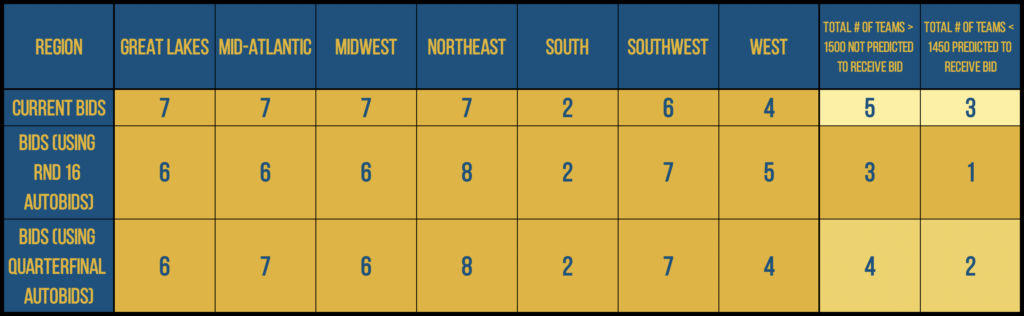

So how can we go about solving this problem, and increasing the chances that the 48 teams at USQ Cup are the 48 best teams in the country? One simple and fair method would be to resurrect a USQ policy used as recently as 2017. Prior to USQ Cup 11, one “autobid” was given to each region for every team from that region that made it to the Sweet 16 at nationals the year prior. These 16 bids were subtracted from the total amount of available bids to nationals, and then the remaining bids were distributed based on the relative size of each region, just as they were this year. This resulted in regions with stronger teams receiving a relatively higher amount of bids, thereby meaning that the presence of perennial contenders like the University of Texas or University of Kansas wouldn’t keep lower-tier teams in their regions from qualifying. This autobid system went the way of the bristled broom when the college/club split occurred. Although no official rationale behind the death of the autobid was ever given, it seemed that it was put on hold as the separate college and club tournament formats were worked out. Since that time, however, the autobid policy has remained tabled, seemingly replaced by the at-large bid system. The at-large system has helped mitigate some of the issues that an uneven bid system creates, but is far from perfect in a college system where few teams travel far outside their own regions.

Back when regional autobids were distributed, World Cups (and USQ Cups) featured a much larger array of teams than the 48-team structure laid out for USQ Cup 13. This season, if the same system of giving 16 autobids was used, those autobids would account for a full third of the total bids being given to Cup. To adjust, eight total autobids would scale nicely to a tournament this size—although that raises the question of how those bids should be distributed. A straightforward system would just give an autobid for every team that made the quarterfinals. That would work simply enough, but also only takes into account the eight teams that make the quarterfinals. The inherent unpredictability of brackets, and the small sample size of these teams, could result in a high variance in autobid distribution from year to year if the bracket happens to break friendly for a particular region. An alternative system would give half an autobid to a region for each team that makes the round of 16. This would preserve that cutoff for teams and likely make the autobid distribution a little more predictable from year to year, and would have the added benefit of better breaking ties in the Huntington-Hill formula USQ uses to distribute bids when two regions have the same amount of registered teams. Either way, either of these autobid distribution systems would likely produce a more competitive and equitable distribution of bids to future USQ Cups, as shown below:

While these “numbers” and “stats” may make a logical argument for the return of the autobid, they completely miss out on what may be the most poignant reason for the needed revival of the autobid. Back in the days when the autobid was still extant, eliminated teams had something to do with their Sunday other than hangout with their teammates and see how many beverages they could sneak into the complex in their water bottles. In the age of autobids, those teams would get together and root for their in-state rivals to win just one more game, knowing that if they did, it would not just help that team, but their whole region come bid allocation next year. Sunday morning games were filled with regional cheering squads in ways that they just aren’t now that the games only carry stakes for the two teams involved. These autobid games brought fan engagement and regional pride to our sport in ways that have yet to be matched since 2017.

So whether you’re in it for the math, the fairness, or in it for the intra-regional spirit these bids can bring, the autobid has sat on the shelf for long enough—let’s bring it back.

About Joshua Mansfield

A native of Cincinnati, Ohio, Joshua Mansfield began playing quidditch when he founded the Tulane University team in 2013. He currently plays for Texas Hill Country Heat and serves as the Gameplay Director for Major League Quidditch. Additionally, he is the third-largest consumer of cilantro in the greater New Orleans area.

One Comment