Antwerp QC, Much of Belgian Core, Leaves Competitive Quidditch

Due to some odd quirks of the IQA World Cup format, we saw two matches between the two best teams at the tournament on day one. When Australia and the United States faced off, the Aussies quickly built a commanding 40-0 lead, but the slightly-favored American side made a comeback, eventually tying the score at 60-60 before U.S. seeker Tyler Trudeau was able to pull the snitch for a 90*-60 victory. Due to seeding, the two teams faced off again in the quarterfinals, sending the loser home without a chance at a medal. In this rematch, it was the Americans who were able to win the quaffle game, holding a 40-point edge before Harry Greenhouse was able to quickly pull the snitch for a 100*-30 victory. What changed between these two matches? How was the United States able to push Australia out of snitch range in the second game, when they themselves had been pushed out of snitch range early in the first game? Let’s look at the film to find out.

In my opinion, the difference between these two games came down to the way the Americans were able to execute offensively. Going into their pool-play match, USNT had run through prior competitors Ireland and Italy, winning the two games by a combined 310 quaffle points. This sort of domination tends to come from teams that can master beater play and whose chasers can simply run through the opposing team’s quaffle defense. Whether intentional or not, the Americans came out in a way that suggested they could do similar things to the Australian quaffle defense. Unfortunately for them, they ran into the team in the tournament with the strongest physical defense. While most of Australia’s 40-0 lead was built by preventing the Americans from getting the no-bludger offensive possessions they covet, the lead was held by the continued ability of the Australian chasers to stop the Americans from scoring on those same no-bludger possessions. Their task was made easier, however, by poor teamwork between the American chasers, leading to mostly attempts at solo drives.

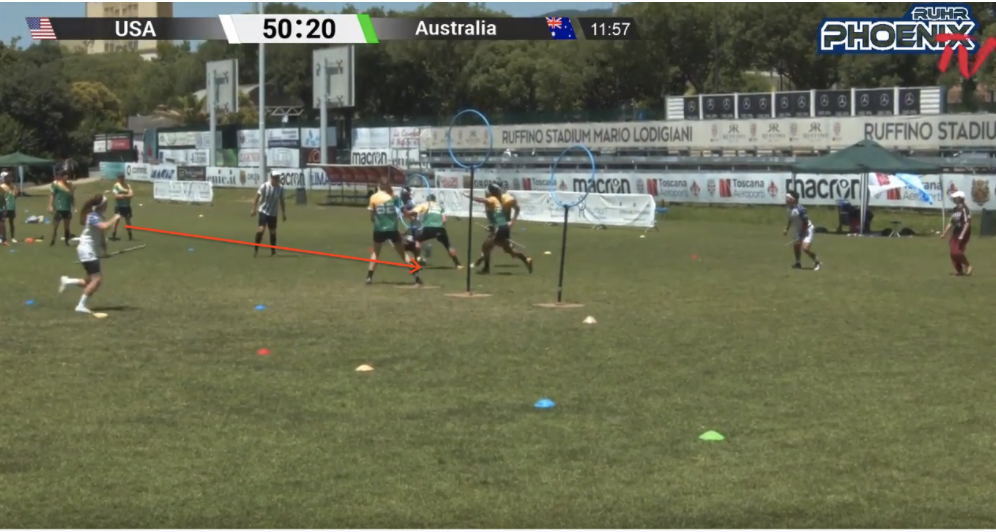

In the above play, Lulu Xu is about to take out both Australian beaters to create a no-bludger situation for the United States. Seeing his chance, Sam Haimowitz begins his drive down the right side. However, if you look at the picture, all four American quaffle players are near the midline, with Lindsay Marella only slightly in front of the quaffle line. Haimowitz then charges to the right, with Greenhouse and Marella charging to the left. However, with no player even threatening behind the hoops, it allows the Australian defense to remain compact. Because all of the cuts come from the front of the hoops, the collapsed Australian defense is able to take away every good passing option:

Both Marella and Greenhouse cut to essentially the same spot, and the two of them are on the exact same line from Haimowitz. Jayke Archibald is actually spaced in a more appropriate spot in the middle of the pitch, but still isn’t a viable passing option with Haimowitz’ positioning; executing a pass to Archibald from that angle would be nigh-impossible. Due to a lack of options, Haimowitz is forced to drive and while he does draw a card from this, the Australian beaters have the time to reset and the U.S. fails to convert. You can see similar types of plays throughout this game, as a consequence of poor positioning and offensive teamwork.

A minute later with the score unchanged, Greenhouse gets a great opportunity in the open field with all Australian beaters beat out of the play. He correctly begins to run the break with Haimowitz streaking down the left side:

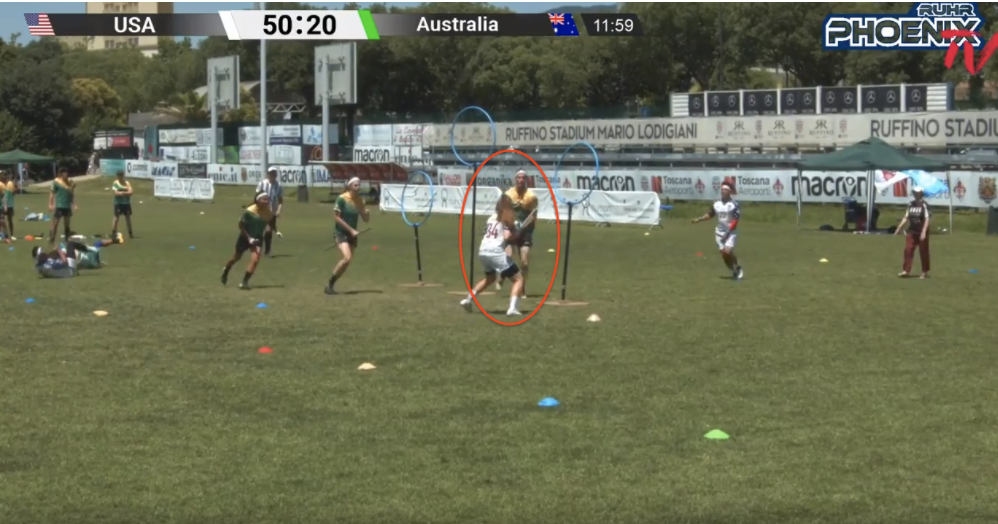

Greenhouse shakes the first defender, then he freezes the second with a pump fake. Meanwhile, Haimowitz has beaten his defender and takes a step inward to put his body between his defender and the hoop, preventing his defender from denying him the ball. As the second defender commits to the hit, Australia’s Neil Kemister puts his head down and misses the opportunity to stop Greenhouse’s passing lane: the on-ball defender fails to restrict the path and the keeper in a neutral position respecting the shot:

A bullet pass from Greenhouse to Haimowitz here should succeed, albeit this is a play with a very low margin for error. Greenhouse continues to drive forward in an effort to widen the window, but in doing so two things happen:

Firstly, with Greenhouse wrapped up, generating power on a hypothetical pass to Haimowitz becomes much more difficult. Secondly, because Greenhouse has closed distance towards the hoop vertically but strayed a bit horizontally, his ability to shoot the ball from here is greatly compromised, which means Australian keeper Callum Mayling can sit on this passing lane. Unable to break free from the tackle, Greenhouse loses his broom and the possession ends.

Before analyzing the adjustments that let them succeed, let’s look at why the US’s best chance at scoring early in game two failed.

Augustine Monroe has the ball, and jukes his point defender, opening the scoring threat.

Monroe steps up and forces the Australian beater to respect him, drawing in the beat just as he passes off the quaffle.This simplifies the possession to Simon Arends and Kaci Erwin against the Australian quaffle defense.

Arends pushes forward and tries to float a pass to Erwin, who is camped by a hoop. Because of her positioning, Arends’s choice to float a pass through three defenders–all relatively close to the hoop–is unlikely to find success, and the back defender intercepts his pass. However, with the Australian beater readying his throw, this is Arends’s best option here. Arends needed Erwin to stretch back behind the hoops more; that shift would either draw a defender towards Erwin and open a shot for Arends or or leave a much more open passing lane.

It is not surprising to see the United States come out somewhat tight in their big knockout game. However, they soon got more comfortable and began to play a much more cut-and-pass oriented game:

With a chaser and beater both pressing heavily out on Archibald, he sees the opportunity and floats a pass down to Nick Marino. Marino times his next move based on the Australian beater’s rebound recovery, and finds a pass behind the hoops to Haimowitz:

Crucially, Haimowitz doesn’t cut directly to the hoop, but instead to the open space behind the hoop, and Marino finds him in-stride. Because Haimowitz doesn’t cut to the hoop, Mayling is not in a good position to stop the drive and Haimowitz gets the momentum to drive into open space:

Now, as Australia shifts in an attempt to get into optimal position,, Haimowitz can score and getst the Americans on the board.

A couple of minutes later, the Americans demonstrate what I feel is their best display of teamwork in the entire match. Archibald takes advantage of the opposing beater’s aggression, quickly passing off to Julia Baer before the beat comes in:

Baer wastes no time and finds Haimowitz behind the hoops who quickly draws two defenders.

Haimowitz should probably have looked to pass to Marino here for an easy dunk, but instead fires the shot. However, because the field is spread out so well, Marino is easily able to pick up the rebound and makes the best of this play:

Marino’s objective is now to manipulate the defense to open up the space near the medium hoop. Marino begins a loopy run towards the left hoop and the entire Australian defense shifts to stop him, losing Haimowitz in the process. Haimowitz sees his opportunity and cuts to the hoop as Marino fires a perfect pass for an easy goal, giving the American side their first quaffle lead.

Our final example of how the American offensive tweaks beat Australia will come as the United States pushes Australia to the verge of snitch range as the Americans use great off-ball movement to create an easy dunk for Luke Langlinais on a power play:

First, note just how well spaced the U.S. side at the start of the power play, which is optimal since this directly follows a penalty restart. With Greenhouse holding the quaffle, every other American chaser shifts to open up the defense. Trudeau will set a pick to open up all lanes from Greenhouse. This forces Mayling to step up to prevent a Greenhouse drive. Simultaneously, Baer cuts behind the hoops, forcing the final chaser to slide with her to close that passing lane.

With all three Australian defenders now occupied, Greenhouse has ample room to take a shot but he also sees the wide open Langlinais on the side. AfterBailee Fields eliminates the only beater, nothing is there to slow Langlinais’s cut, as Greenhouse finds the assist to give the Americans their fifth goal of the game in a complete team effort:

Chaser power plays are often considered weaker than beater power plays, but the American side here showed a textbook example of how they can be every bit as effective, even against as stout of a defense as Australia’s.

While these adjustments brought USNT success, there was still room for improvement that would develop alongside this team’s chemistry. In a wild scramble, Archibald kicks the ball deep into the Australian zone as the chaos ensues:

Haimowitz’s hustle helps him win the race to the ball, and the entire Australian defense sucks in to try to mark him, which leaves Marella open for a sneaky backdoor cut.

Unfortunately, the pass comes in a little low and Australia’s James Osmond makes a heads up play and sees this coming, so he crashes in on the open Marella.

Marella gathers herself and takes the shot, but Osmond has closed into position to block, recover the quaffle and snuff out the possession. Still, this entire play is a marked improvement from the Americans performance in their first matchup; Marella can’t be blamed for Osmond making a great read and play in the heat of the moment.

However, this play demonstrates an opportunity for the USNT and quidditch teams in general moving forward: making one more pass. Often times, a player will have a really nice opening to score,like Marella had against Australia. However, those opportunities often coincide with a defensive scramble–like Osmond’s play–that opens up an even easier opportunity. Let’s take a look at a quick play from the Golden State Warriors in basketball:

Back on the subject of quidditch, Marella did have another option other than shooting against Australia: in the chaos of the defense crashing in on her, Martin Bermudez Jr. is left wide open behind the hoops. If she were to quickly fire a pass (or even bounce a pass on the ground to him), Bermudez would have an uncontested dunk here. This missed opportunity speaks to the overall difference between a team of great players and a great team: the power of one additional pass.

Looking back, US National Team still has room for improvement but these shortcomings are much smaller than they were after their first game against Australia., Their change in performance evinces an attitude adjustment throughout the entire roster, as we saw selfless plays from every player leading to much improved offensive flow. By adjusting the attitudes of the entire team, we saw the United States make massive improvements between the two days of the tournament and, in the process, helped the Redeem Team recapture the world championship.

Archives by Month:

- May 2023

- April 2023

- April 2022

- January 2021

- October 2020

- September 2020

- July 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- August 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- November 2017

- October 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

Archives by Subject:

- Categories

- Awards

- College/Community Split

- Column

- Community Teams

- Countdown to Columbia

- DIY

- Drills

- Elo Rankings

- Fantasy Fantasy Tournaments

- Game & Tournament Reports

- General

- History Of

- International

- IQA World Cup

- Major League Quidditch

- March Madness

- Matches of the Decade

- Monday Water Cooler

- News

- Positional Strategy

- Press Release

- Profiles

- Quidditch Australia

- Rankings Wrap-Up

- Referees

- Rock Hill Roll Call

- Rules and Policy

- Statistic

- Strategy

- Team Management

- Team USA

- The Pitch

- The Quidditch Lens

- Top 10 College

- Top 10 Community

- Top 20

- Uncategorized

- US Quarantine Cup

- US Quidditch Cup